- Home

- Gita Nazareth

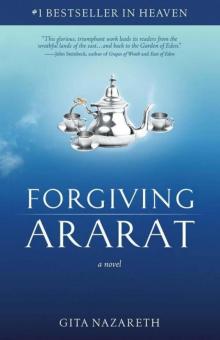

Forgiving Ararat

Forgiving Ararat Read online

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission from the author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover and interior design by Frame25 Productions

Kindle layout by Kindle Wizards

Cover art by Albert H. Teich, Vinicius Tupinamba, and

Aaron Amat, c/o Shutterstock.com

Bette Press, LLC

P.O. Box 1139

Kennett Square, Pennsylvania 19348

www.forgivingararat.com

Library of Congress Control Number 2009910405

ISBN 978-0-9825605-1-8

First Edition

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Contents

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

PART TWO

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

PART THREE

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

PART FOUR

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

That art thou . . .

“I think it well you follow me and I will be your guide and lead you forth through an eternal place. There you shall see the ancient spirits tried.”

—Dante, The Inferno

I do not remember anymore.

Were my eyes blue like the sky or brown like fresh-tilled earth? Did my hair curl into giggles around my chin or drape over my shoulders in a frown? Was my skin light or dark? Was my body heavy or lean? Did I wear tailored silks or rough cotton and flax?

I do not remember. I remember that I was a woman, which is more than mere recollection of womb and bosom. And for a moment, I remembered all my moments in linear time, which began with womb and bosom and ended there too. But these are fading away now, discarded ballast from a ship emerged from the storm. I do not mourn the loss of any of these; nor am I any longer capable of mourning.

I was named Brek Abigail Cuttler. I have just learned that what is is what I knew once as a young child and glimpsed twice in twilight as an adult. I have chosen what is from what is not. And I will always be.

PART ONE

1

* * *

I arrived at Shemaya Station after my heart stopped beating and all activity in my brain irreversibly ceased.

This is the medical definition of death, although both the living and, I can assure you, the dead, resent its finality. There’s always cause for hope, people argue, and sometimes miracles. I myself used to think this way, but my views have changed. I’ve discovered, for example, that even if a miracle fails at the final moment to keep you alive, there’s still the possibility one will come along later, at the Final Judgment, to keep you from spending the rest of eternity wanting others dead.

I didn’t know I had died when I arrived at Shemaya Station, nor did I have any reason to suspect such a thing. Nobody announces that your life’s over when it is. As far as I was concerned, my heart was still beating and my brain still functioning; the only hint that something out of the ordinary had happened was that I had no idea where I was or how I’d gotten there. I simply found myself alone on a wooden bench in a deserted urban train station with a high arched dome of corroded girders and trusses and broken glass panels filthy with soot. I had no memory of a train ride, no memory of a destination. A dimly lit board in the middle of the waiting area showed arrival times but no departures, and I assumed, as most who come here do, that the board was broken or there were problems with the outbound tracks.

I sat and stared at the board, waiting for it to flash some piece of information that would give me a clue about where I was or at least where I was going. When the board refused to divulge anything further, I stood and gazed down the tracks, as anxious passengers do, hoping to see some movement or a flicker of light in the distance. The rails vanished into utter darkness, either a tunnel or a black starless night, I could not tell which. I glanced back at the board again and then, forlornly, around the station: ten tracks and ten platforms, all vacant; ticket counter, newsstand, waiting area, shoe shine, all empty. The building was completely quiet: no announcements over the loudspeakers, no whistles blowing, brake shoes screeching, or air compressors shrieking; no conductors shouting, passengers complaining, or panhandling musicians playing. Not even the sound of a janitor sweeping in a far corner of the building.

I sat back down on the bench and noticed I was wearing a black silk skirted suit. The sight of this suit made me feel a little safer and a little less alone. I had been a lawyer during my life, and lawyers always wear suits to feel more confident and less vulnerable. This particular suit was my favorite because it made me feel the most confident and least apologetic as a young woman when I entered the courtroom. I smoothed the skirt on my lap, admiring the heavy weight and rich texture of the fabric and the way it glided over my stockings. It really was a beautiful suit—a suit that attracted glances from colleagues, opposing counsel, and even men on the street; a suit that said I was a lawyer to be taken seriously. The best part of all was that I had found it on a clearance rack at an outlet store—a power suit and a bargain. I loved that suit.

So there I was, sitting all alone on a bench in this deserted train station, infatuated with my black silk suit, when I noticed some small stains on the shoulder and lapel of my jacket. The stains were crusty and yellowish-white, and I assumed I had probably spilled cappuccino on myself earlier in the day. I scratched at the stains with the edge of a polished but chipped fingernail, expecting the aroma of coffee to be released; but a very different scent floated into my consciousness instead: baby formula.

Baby formula? Do I have a child...? Yes, of course...a child...a baby daughter...I remember now. But what’s her name? I think it begins with an S...Susan, Sharon, Samantha, Stephanie, Sarah...Sarah? Oh yes, Sarah.

But as hard as I tried, I couldn’t remember anything about Sarah’s face or hair, or the way she giggled or cried, or the smell of her skin, or the way she might have squirmed when I held her. I remembered only that a child had grown inside of me, had become part of me, and then left to join the world around me—where I could see her and touch her but not protect her the way I did when she was inside me. And yet, even though I couldn’t remember anything about my own daughter except her name, I wasn’t bothered by this in the least. Sitting there on the bench in Shemaya Station, I was far more worried about the stains on my jacket—terrified somebody would see what I had allowed to happen to my favorite “I belong” black silk suit.

I scraped more vigorously at the stains. When they wouldn’t go away, I lapped at my fingertips to moisten them. But instead of dis

appearing, the stains grew larger and changed in color from yellowish-white to deep wine red. The transformation was subtle at first, like the change from clear afternoon to streaked and pigmented sunset.

The dye’s beginning to run...that’s why the suit was on the clearance rack.

But the stains started behaving differently too. They liquefied, sending crimson streaks down my jacket, skirt, and legs. This fascinated me. I dabbed my fingers in the red fluid, tentatively at first, like a child given a jar of paint, then with growing confidence, drawing two little stick figures with it beside me on the bench—a mother and her young daughter. The liquid felt warm and viscous and tasted pleasantly salty when I put a finger to my tongue. A pool of it gathered on the concrete floor of the station, and I slipped off my heels and tapped my toes in it, lost in the creamy sensation.

In the middle of all this, an old man walked up to my bench and sat down beside me.

“Welcome to Shemaya,” he said. “My name is Luas.”

Luas had moist, gray eyes, as if he were always thinking something poignant, and an annotated, gentle sort of frog’s face, flabby and wise like a worn book. The face seemed familiar, and after a moment I recognized it as the face of my mentor, the senior lawyer who had hired me out of law school.

Now what was his name...? Oh yes, Bill, Bill Gwynne. But the old man sitting next to me said his name was Luas, not Bill.

Luas welcomes everybody to Shemaya. He appears differently to each of us, and to each in his own way. He might be an auto mechanic or a teacher to one, a father or a preacher to another, or maybe a madman or all of these combined. In Shemaya, we dress each other up to be exactly who we expect to see. For me, Luas was a composite of the three older men I had adored during my life: he wore a white shirt with a tweed blazer that smelled of rum pipe tobacco, the way my Grandpa Cuttler’s clothes smelled; and, as I said, he had Bill Gwynne’s flabby face; but when I showed him my feet and my left hand, all covered in red, helpless like a little girl playing in her spaghetti, he flashed my Pop Pop Bellini’s knowing smile as if to say: Yes, my granddaughter, I see; I see what you’re afraid to see, but I’ll pretend not to have noticed.

“Come along, Brek,” Luas said. “Let’s get you cleaned up.”

How did he know my name?

I looked down again, but now my clothes were gone—my black silk suit and cream colored silk blouse, my bra, panties, stockings, and shoes. They had never been there actually. There had been only the idea of clothes, as I was only an idea, defined by who I’d insisted on being during the thirty-one years of my life. Only my body remained, naked and covered with blood. I knew now the red liquid was blood, and that it was my blood, because it was spurting through three small holes in my chest, and because it felt warm and precious the way only blood feels. Suddenly my perspective shifted, and it seemed as though I was watching it all from the opposite bench.

Who is this woman? I wondered. Why doesn’t she put her fingers in the holes and stop the bleeding? Why doesn’t she call out for help? She’s so young and pretty, she must have so much to live for. But just look at her sit there—she does nothing but watch, and she feels nothing but pity: pity for the platelets clotting too late, pity for the parts of her body that had once been the whole; and there—see how her brain flickers, losing reasoning first, then consciousness, contracting her muscles to force the blood back to her heart, slowing the beats, slowing the respiration, ordering the mass suicide of millions of cells in a wasted attempt to prolong her life. Listen. The roar of nothingness fills her ears.

Luas removed his jacket and wrapped it around my shoulders. I was crying now, and he hugged me like the granddaughter I might have been. I was crying because I remembered a past that existed before Shemaya Station and Luas, before the baby formula stains and the blood. I remembered my eyes, Irish green like my father’s, and my hair, long, thick, Italian black like my mother’s. I remembered the empty right sleeves of my clothes: pinned back, folded over, sewn shut. I remembered people wondering—I could see it in their faces—what an eight year old girl could have done to deserve all those empty right sleeves? I remembered wanting to tell them, to remind them, that God punishes children for the sins of their parents.

Yes, for one brief and unbearable moment, I remembered many things when I arrived at Shemaya Station. I remembered crayfish dying in the sun and the cruelty of injustice. I remembered the stench of decaying mushrooms and the inconceivable possibility of forgiveness. I remembered the conveyor chain on my grandfather’s manure spreader amputating my right forearm from my elbow and flinging it into the field with the rest of the muck. I remembered the angelic face of my daughter, Sarah, just ten months old, young and fresh and precious like blood. I remembered formula dripping from her bottle down the empty right sleeve of my suit and the pinch of guilt for leaving her at the daycare that morning and the punch of guilt for feeling relieved. I remembered dust on law books and the bitter taste of coffee. I remembered telling my husband I loved him and knowing I did. I remembered picking up my daughter at the end of the day and her squeals of delight when she saw me, and my squeals of delight when I saw her. I remembered singing Hot Tea and Bees Honey to her on the way home and wondering what my husband had made for dinner, because he always makes dinner on Fridays. Most of all, I remembered how comfortable life had become for me...and that I would do anything...give anything...stop at nothing...to make it last.

And then my memories vanished, as if the plug had been pulled on time. There was just baby formula turned to blood, everywhere now, all over my face, neck, and stomach, streaming down my elbow and wrist, streaming down the stump of my right arm, turning red my legs and feet and toes, washing away my life and spilling it onto Luas, painting us together in an embrace, soaking through his jacket and shirt, spreading across his face, pooling onto the floor and clotting into ugly red crumbs around the edges.

This is how I arrived at Shemaya Station when I died.

And somewhere in the universe, God sighed.

2

* * *

Luas led me from the train station to a house not far away. We followed a dirt path through a wood, across pasture, a garden, an apron of lawn. The city I’d imagined beyond the walls of Shemaya Station didn’t exist. We were in the country now.

The sky as we walked was moonless, dark violet and iridescent like a pane of stained glass. Luas led me on in silence, supporting me when I stumbled. I was still stunned from seeing myself bleed to death. Every few yards the weather raged between the extremes of hot and cold, wet and dry, as if even the heavens were stunned too and couldn’t decide what to be and so were all things at once. I felt no physical pain. In an obscure corner of memory my torso throbbed and my nerves shrieked—but these were distant sensations, recollections more than feelings. More immediate was the dampness of the ground against my feet, the changing temperature of the air on my skin, the opalescence of the earth and trees. These were present sensations and the sum my consciousness could bear.

The house to which Luas led me had a broad porch with a white balustrade and wide green steps. An octagonal lamp hung from the ceiling projecting blocks of light onto the lawn, some of it green and leafy and the rest frozen over with ice and snow. The house reminded me of my great-grandparents’ house along the Brandywine River in northern Delaware with the same threatening Victorian turret and gables and pretty scrollwork along the eaves and trim, like so many large homes built in the nineteen twenties. Everything about it was permanent and massive, a bulwark against fate and time: the heavy red brick and fieldstone, the slate roof, the tall windows and ceilings, the thick porch columns and solid brass doorknobs. Even the trees on the lawn and the hills beyond the trees were eternal and massive. It was too dark to see all these things, but I knew they were there in the same way I knew I was there.

On the porch stood an old woman waving excitedly in our direction. Luas squeezed my hand and stiffened to help me up the steps.

“Our guest has finally arr

ived, Sophia,” he announced.

They exchanged polite hugs the way older couples tend to do, and I braced myself for the old woman’s shrieks when she realized her husband had brought home a nude woman half his age and covered in blood; but for all the scandal and gore of my appearance, you’d have thought this was the condition in which all her guests arrived. She rushed forward and wrapped herself around me, carelessly staining her blue chamois dress with my blood before peeling herself just far enough away to see my face and caress my cheeks, laughing and sobbing, stroking my hair, her hands shaking with emotion.

“Thank you, thank you, Luas,” she said, breathlessly, almost crying.

Luas winked at me and walked back down the steps into the darkness from which we’d come, leaving a trail of bloody shoeprints on the green planks.

They’re obviously mad, I thought.

Sophia had an ethnic face, Mediterranean and expressive and proud, with an angular forehead and thin lips that curled like a faded purple ribbon around a box of secrets. Her tarnished silver hair coiled into a bun, and she spoke with an Italian accent that added syllables to the English words.

“Oh, Brek,” she whispered. “My precious, precious child.”

“Nana?”

The word exhaled from my lungs with a whimper, accompanied by the recollection of an old photograph, the face of my great-grandmother, Sophia Bellini, my Nana. She’d died from a stroke when I was three years old.

“Yes, child, oh yes,” she said.

My only memory of her was from our final time together at the funeral home. I’d thrown a tantrum when my mother made me kiss Nana Bellini goodbye in the open coffin. Above my screaming, I remembered a sound, plastic and horrible, produced when my shiny black shoe fell from my foot and landed squarely on Nana’s pallid forehead. The shoe bounced once and lodged in her hair like a tiara. I remembered the slap of my mother’s hand across my face, and that Nana’s eyes did not open, and that her smile, serene and insane, did not change.

Forgiving Ararat

Forgiving Ararat